Pilgrimage to the Source of the Ganges

‘How tacky,’ we thought, of the cheap trinkets and plastic containers hung up in an endless row of stalls and spilling out into the narrow cobblestone walkway. It seemed that mass-produced souvenirs were not just for the likes of Delhi or the Taj Mahal, but also the remote, far-flung corners of India. Here we were in Gangotri, a tiny mountain town west of the Nepalese border. We had taken an 8 hour bus, another 5 hour bus, and a 3 hour taxi (for lack of bus) to escape the dense masses of Delhi — only to discover that Gangotri is a holy pilgrimage site attracting bus-loads of Indian tourists every day.

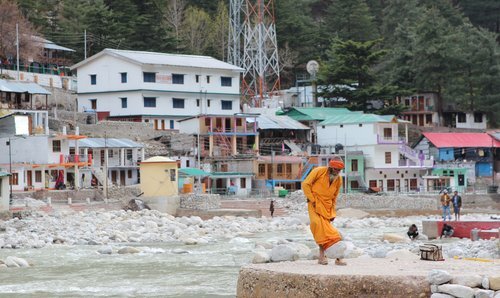

Nestled at the foot of a valley in the Indian Himalayas, Gangotri is home to a natural waterfall where Lord Shiva supposedly created the holy Ganges river. Many Hindus make an annual visit to Gangotri for a ritual bath at the temple steps, taking home a plastic bottle or bronze container of Ganges water as their prized souvenir (hence the endless stalls). As we arrived, the town bustled with many such pilgrims—men in puffy jackets and perched toques, scarves wrapped around like blankets, and women shivering in colourful saris, midriffs exposed in the traditional way despite a chill in the air. Such images distinguished it from the many mountain towns we'd visited in other faraway places, as did its unique smell of incense mingling with pine.

We’d come to Gangotri on a pilgrimage of our own, but it was Mount Shivling we were after. We planned to trek to base camp by way of Gaumukh Glacier—the very source of the sacred Ganges—with the hopes of making an additional day trip to the base of Meru. Indian bureaucracy, however, had other plans. As we discovered at the Gangotri National Park office in Uttarkashi, permits would only be granted to us as far as Gaumukh; venturing any further, Shivling base included, required the accompaniment of a registered guide. We had come with all the essentials to trek independently—tent and stove and topo map included—and wanted neither the extra expense nor the third-wheel company of a guide. We paid for permits to Gaumukh, but the thought of standing within striking distance of Meru without seeing its famed shark fin tested my temper with national park officials. Stunningly intimidating, Meru rises to a fin-like point that slices through clouds at 6,660 m. First summited on Conrad Anker, Jimmy Chin, and Renan Ozturk’s third attempt, and requiring a testing combination of top level rock and ice climbing techniques, the mountain has been a symbol of perseverance to many climbers. For me, it’s been inspiration to learn rock craft. And though we left the office without the permit we wanted, we had a name — we trekked 14km to find the elusive Officer P.S. Panwar and state our case.

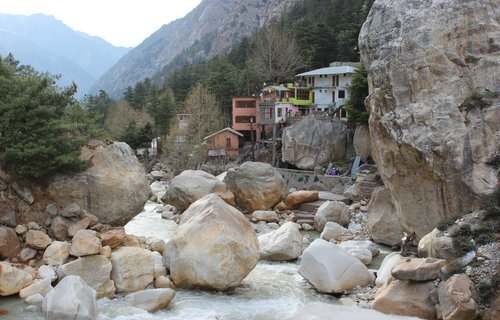

The trail to Gaumukh starts a stone’s throw away from the Gangotri temple [map at bottom]. With packs strapped on tight, we wove our way through the river bathers and temple worshippers, and saffron-clad babas, and up a formidable set of steps. Sweaty and short of breath 5 minutes into the trek, I felt the impact of altitude (luckily, the pressure headache that settled in as we climbed higher vanished after the first night of sleep at 4000m). The entire journey was on a well marked stone-and-gravel path that follows the river valley. Though a fair amount of altitude is gained in one day (unless one camps halfway at Chirbasa to acclimatize) the vertical gain is fairly gradual. Even so, most others were making the journey aboard mules, or with a convoy of luggage-bearing porters in tow (though we did also cross paths with several saffron-clad babas walking their way towards enlightenment with bare feet). As we ventured further into the curving valley, stunning peaks revealed themselves one after the other, perspectives ever changing until finally, we were overlooking the yurts and ashram of Bojwasa, the peaks of Parbat I and II painting a monumentally stunning backdrop.

We set up camp at a hidden spot along the river then proceeded to find Mr. P.S. Panwar. After poking our heads around, we found him in the far corner of a dimly lit room, sitting on the edge a metal bed in an army green military jacket. I delivered my well-rehearsed plea for a special permit but his reactionary head shake crushed our dreams immediately. We tried to explain that we were experienced trekkers, that safety was our priority and responsibility was ours alone, and even offered to join (and pay) the guided group we’d met on the trail that day. But in the end there would be no exception to the park’s new rules. Permits could only be applied for in Uttarkashi some 50 km (an 8 hour hike and 3 hour taxi) away and without that piece of paper, we were not allowed past Gaumukh.

Solace came in the form of daal. We were invited to dinner at the ashram, where long burlap runners were laid out in rows and seats marked out by metal plates. Not long after shoes were removed and places were taken, buckets of daal and rice, giant pots of tea, and endless roti were doled out. The hot food warmed my cold hands and as quickly as it all started, a chorus of loud belches signified the end of the meal. Bellies full, we curled up in our little tent by the river, nothing but stars overhead.

By 8am, sun streamed over the valley and warmed the tent enough to coax us outside. Unzipping the door unveiled the stunning Parbats, still standing right where we’d bid them goodnight. After coffee and oatmeal with a view, we made the 5km trek to Gaumukh, still hopeful we might be able to traverse the glacier and slip past the permit checkpoint. But Mother Nature always has the final word and early that morning, a rockslide shifted the river upstream; the Ganges flowed wildly where an easy crossing had been, the water milky grey with debris and a returning party trapped on the other side. When we saw a team of porters with several lengths of rope sent to help the stranded, we accepted our fate with more ease than the night before. The power and unpredictability of nature has my wholehearted respect, unlike bureaucracy inflexible to logic or reason.

After a day rock hopping, sketching, and lounging by the river, a light snow herded us into our tent for the night. We warmed ourselves with cups of tea and picked up our ongoing conversation about spirituality without religion by questioning the role religion plays in relation to tourism and the Gangotri National Park service. It seemed to us that the park caters to religious pilgrims being ferried by porters and mules to collect Ganges water from the source (a quickly receding glacier, I should mention) over independent trekkers because they better fuel the local economy. We couldn't comprehend why the park supports visitors who don’t understand the concept of packing out what they carry in, who ride mules so hungry they resort to eating cardboard and rely on 13 year-old porters with their body weight in luggage strapped to their heads (like so)—over mountain lovers who simply wish to revel in the park’s natural wonders, and who would leave no footprint. Shouldn’t a national park’s mission be to enable such elemental desires and protect the environment from disregard?

We broke camp and trekked back to Gangotri the next morning, dampened spirits brightening with each new scene unfolding in the valley. We stopped for water on the stretch after Chirbasa and, by chance, I looked back over my shoulder. I saw a tiny shark fin in the negative space between two peaks. Could it be? Consulting our topo confirmed that it was, indeed, a very distant glimpse of the symbolic Meru.

The sun was setting on the other side of the sky as we entered town and crossed the familiar rusty green bridge to our guesthouse. Gangotri seemed different to me now, though we were greeted by familiar faces. Shorbeer met us at the bridge, welcoming us back to his guesthouse by offering to carry my bag (I didn't want to seem ungrateful, but what's another 10 meters after 36km?). Sudeep—fellow traveller and author—also waved us welcome. We had met him the day before the trek and, in sharing life experiences over dosas, learned the meaning of satsang: a spiritual conversation (sat means "truth"). And so while tourists conducted their rituals on the far side of the river, strangers bumping shoulders in a crowd, we sat down together exchanging news over hot chai as old friends might. Suddenly, what seemed to matter more than unreached places were the relationships made along the way, and the one blossoming with my chosen travel partner. As Sudeep had said over dosas, "it's helping each other move through life," that is important.

Leaving Gangotri the next day, I stopped midway across the iron bridge and took one last look out across the temple. Eyes following the river, I retraced the path we'd trekked until it disappeared behind a faraway bend. The slanting peaks of the valley and the metal beams of the bridge railing seemed to align in cosmic perfection, framing the scene like a postcard. I was caught in a rift—frozen in place by the gravity of a spiritual presence, caught in the current of all that might unfold in three weeks on the road. But Luke, with his long legs, was already miles ahead... so I cinched my pack straps tighter and willed tired legs onward.

In Gangotri, there is an invisible force pulsing in the river, culminating in the cold night air, reverberating in the valley. I cannot begin to explain spiritual energy but it was there on the bridge, in the apogee of a farewell, that I felt it. Perhaps if you make the pilgrimage, you too will find it there.

NOTE TO TRAVELLERS:

Do stay with Shoorbeer and Dalbeer of HOTEL GANGA NIKETAN. Their hospitality is unparalleled, and their restaurant offers an incredible view. | www.apekshaadventure.com | info@apekshaadventure.com

NOTE TO THE SPIRITUALLY CURIOUS:

Sudeep Balain’s book YOU ARE LOVE is available on Amazon.com. It depicts his personal and spiritual journey—from working on in the corporate world and owning a million dollar home in Sam Francisco to spending months in far corners of the world seeking spiritual wisdom from babas, sadhus, gurus, and monks.